Gemæltan, for solo cello and orchestra (2020)

written for Sæunn Thorsteinsdóttir

Premiered on the 29. September 2022 with Sæunn Thorsteinsdóttir, the Iceland Symphony Orchestra and Eva Ollikainen at Harpa/Eldborg (IS)

Nominated for the Icelandic Music Awards 2023 - Composition of the Year (Classical/ Contemporary)

Icelandic-American cellist Sæunn Thorsteinsdóttir enjoys a varied career as a performer, collaborator and teaching artist. She has appeared as soloist with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchester, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Seattle Symphony, Toronto Symphony Orchestra and Iceland Symphony, among others, and her recital and chamber music performances have taken her across the US, Europe and Asia. Sæunn has performed in many of the world’s prestigious venues including Carnegie Hall, Suntory Hall, Elbphilharmonie, Barbican Center and Disney Hall and the Los Angeles Times praised her performances for their “emotional intensity”.

Programme note:

We are living the most rapid change of Earth’s forces that a single generation has experienced. Glaciers, that before moved at geological speed of centuries and millennia, are now vanishing in a lifetime of a single human being. Nature has left geological speed and moves at human speed.

Now we are living in times where leaders of the world meet and discuss how they will observe rising sea level in the next 100 years with melting and vanishing of glaciers. As if that was a normal natural process. Cesar, Ramses II, Alexander the Great and Napoleon, none of them thought they could lift the oceans of the world. Moses split the Red Sea and that was an accomplishment, but that was nothing compared with lifting entire oceans of the world by melting most of the glaciers.

We are living in a new era, a new paradigm of understanding, a new geological era, the Anthropocene, but it feels like we don't comprehend it. We see the facts, the brain takes in the data, but still, it is as if what is happening is not really understood. A scientist told me that he could gather data and measurements, but he would not really understand his findings until others understood them. Understanding is not an individual act; it is a collective culture. If we look at the history of paradigm shifts, we can see that the real shift does not happen until the new ideas are embedded in culture. In stories, in poetry, music, film or visual art.

I thought at first it was odd to make music about a melting glacier. How do you do that? It might be obvious how to capture a melting glacier in words and pictures, but how do you capture a melting glacier with classical instruments?

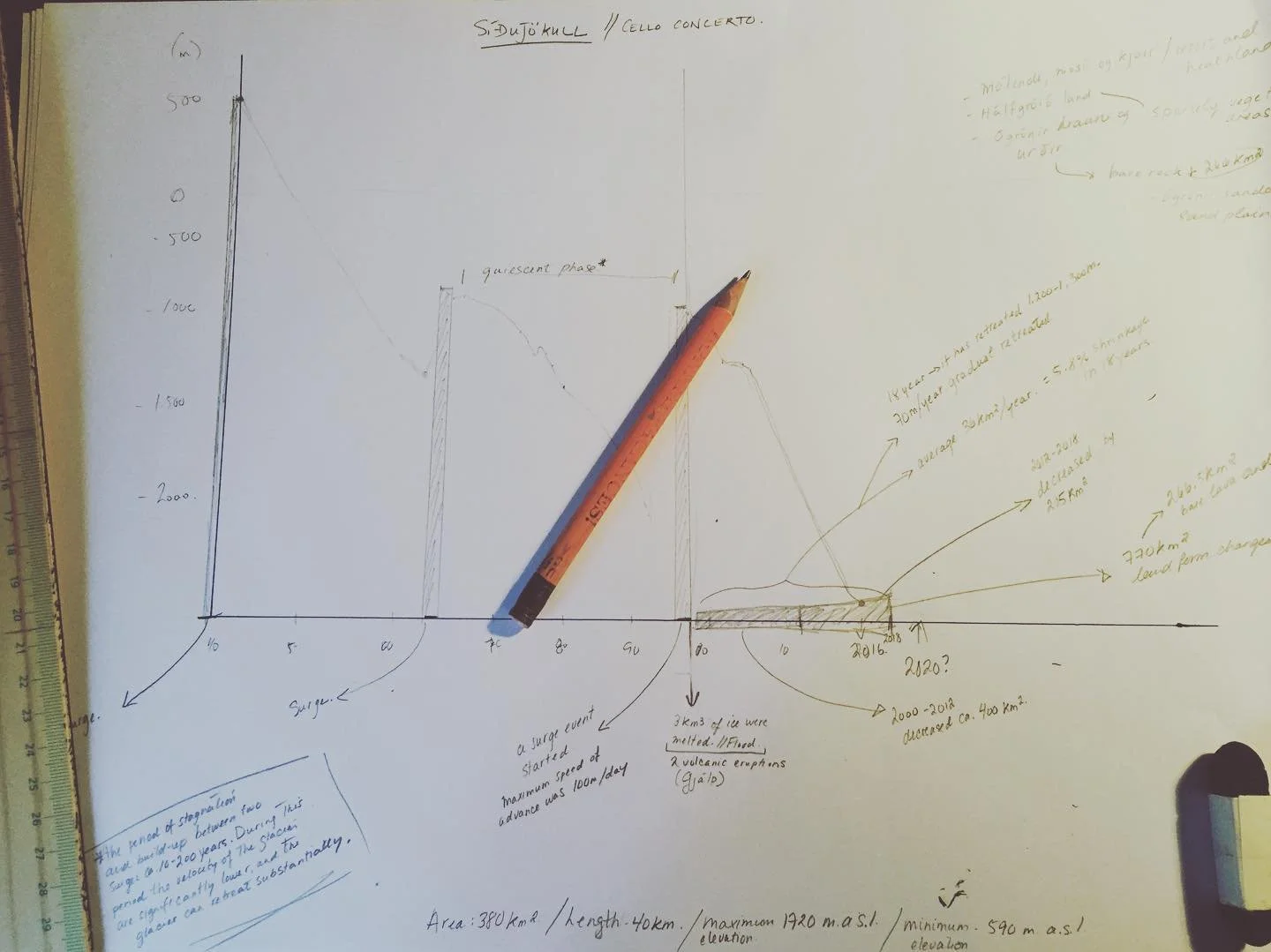

The work Gemæltan began when Veronique found an old map of the area of Síðujökull and compared it with a modern one. The change was alarming. The intention behind Gemæltan is to create awareness of climate change by an abstract representation of the vanishing landscape and the glacial afterglow, with a title and a programme note leading the audience to active listening. The approach is almost scientific; the piece is shaped by climate change. By going through texts and gathering data and information on the location, the behaviour of glaciers and their impact on landscape and ecology. By examining graphs and maps and extracting information to create the time progression of the piece. It then evolved to the idea of writing a cello concerto — with all the possibilities of creating a dialogue between a soloist and an orchestra.

The structure of the work consists of two surges and two quiescent phases - the last being the rapid retreat which leads to the disappearance of the glacier. The composer translates the gathered information by associating them to music parameters, and by defining the role of the soloist and the orchestra. She imagines details of the glaciers as motifs, colours, living materials, textures, and it affects the way she perceives the orchestration. As an example, the water accumulating under the glacier, moving rocks and matter, influenced how the piece shifts from one instrument to the other - intending to create a natural flow and a sense of wholeness.

Surge #1: The cellist is representing the behaviour of the glacier. She creates events which make the orchestra react. This moment is to describe the enormous mass and volume of the glacier moving forward as a unity.

Quiescent phase #1: Retreat: Since the movement forward has stopped, this new phase is represented by a sensation of stillness and a decrease in energy. Even though the glacier is retreating, its inner power is growing for the next surge.

Surge #2: The cellist is gradually passing from the quiescent phase motif (harmonics) to the surge motif (double stops), leading to the cadenza. Which will, gradually "wake-up" the orchestra and lead to a movement of unity (climax).

Quiescent phase #2: Retreat: The landscape is being transformed by the incredibly fast retreat of the glacier. It will lead to its complete disappearance. It is pictured with the drastic changes of colours by the cellist and the orchestra. The contours of the land are lost, and a different landscape emerges. The mood is shifting; the energy is fading, and the volume of the glacier is changing.

The end: The orchestra which represented the glacier has gone - its mass has dissolved. The soloist is now alone, and she expresses the glacier’s reminiscence by using fragments, colours and textures of the previous motifs. There is less and less material left, and the sound is gradually losing its quality and fading into nothingness.

Earth has left geological speed and is changing to human speed. We seem to react at geological speed. Cellist Gunnar Kvaran told me that the violin speaks to the head, it is clever and fast, while the cello speaks to the heart. We are living times of urgency, where we have new data that needs to speak to the heart. The cello might be the perfect medium to speed up the paradigm shift and the call to action. - Andri Snær Magnason, 2020

Vanescere, for solo viola and chamber orchestra (2021)

written for Þórunn Ósk Marinósdóttir

Premiered on the 6. March 2022 with Kammersveit Reykjavíkur, Þórunn Ósk Marinósdóttir and Mirian Khukhunaishvilli at Harpa/Norðurljós (IS)

Myrkir Músíkdagar / Dark Music Days Festival

Þórunn Ósk Marinósdóttir is the principal violist of the Iceland Symphony Orchestra and a founding member of Siggi String Quartet which has been a recipient of The Icelandic Music Award. Born and raised in Akureyri, she later studied viola at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels with Mr. Ervin Schiffer. In Belgium she was the principal viola of the chamber orchestra Prima la Musica and for a period a member of the soloist ensemble I Fiamminghi. Alongside her job at the Symphony, Þórunn performs widely in chamber music,including playing in chamber music recordings, mostly for the Reykjavík Chamber Orchestra. She is a regular guest at chamber music festivals in Iceland including Reykholt Music Festival and Reykjavik Midsummer Music. Her recordings of music by Hafliði Hallgrímsson; Ombra viola concerto with the Reykjavik Chamber Orchestra and Notes from a Diary for viola and piano have been published by the Bad taste record company. Þórunn has performed as a soloist with the Iceland Symphony Orchestra, Reykjavík Chamber Orchestra, Prima la Musica and Sumida Triphony Hall Orchestra in Tokyo. Since 2021 Þórunn and her husband were appointed co-Artistic Director’s of the Reykholt Music Festival. She teaches viola and chamber music at the Reykjavík College of Music and Icelandic University of the Arts.

Programme note:

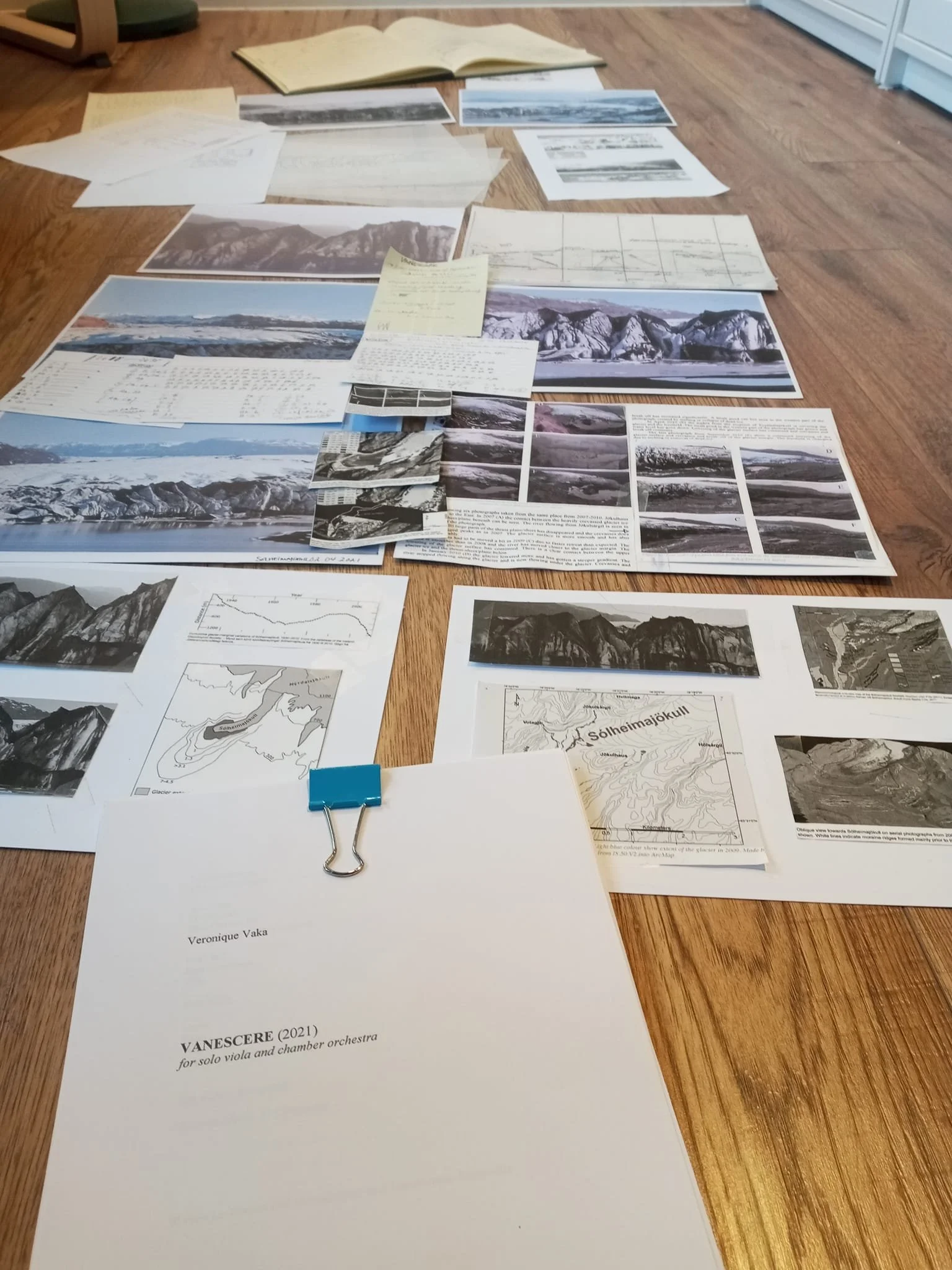

Veronique Vaka has made it her mission to translate nature’s processes into sound. The viola concerto Vanescere follows her luminous orchestral work Lendh, nominated for the Nordic Council Music Prize, and, zooms-in on principles explored in the cello concerto Gemæltan.

Like Gemæltan, Vasnescere takes as its subject the area around the Sólheimajökull glacier in Iceland. Using geographical and geological analyses, Vaka traced the steady erosion of the glacier over the year from September 2020 and was alarmed at the rapid rate of the ice cap’s retreat. Vasnescere is an abstract representation of the harvested data that underlines the speed of the glacier’s destruction, compressing actual time into musical time. In its direct reaction to the science, the work presents the starkest possible musical depiction of the impact of climate change on the Icelandic landscape.

In translating her statistical and photographical data into musical notation, Vaka works in two principle ways. One is the establishment of a temporal grid that compresses the 12 month change in the glacier’s appearance into the course of the concerto’s duration. We hear the glacier’s changing shape in movements by degrees: the shifting of one note in a chord, the twisting or contracting of a texture. Within this, the narrating solo viola steps out of the strict time-lapse to focus or reflect on individual events and gestures.

But the harvested data also controls the music’s surface colour, affecting shifts in instrumentation, volume and general expression. A crevice or waterfall might be imagined as a trill or a glissando; a melodic motif might represent ‘calving’ – a piece of ice breaking off as the glacier’s state alters under pressure. Ultimately, elements of the orchestra lose their ability to sustain a quality of sound altogether – the starkest warning yet of the effects of climate change on Vaka’s generation of Icelanders. - Andrew Mellor, 2022

Holos, for chamber orchestra (2022)

written for Caput Ensemble and Guðni Franzson

Premiered on the 27. January 2023 with Caput Ensemble and Guðni Franzson at Harpa/Norðurljós (IS)

Myrkir Músíkdagar / Dark Music Days Festival

“Through their earnest, skillful and passionate work – including dozens of CD-releases, touring and participation in many of our foremost festivals – Caput has gratified innumerable listeners with their artistically eminent performances of contemporary music by Nordic composers, ever since it was founded in 1987.”

Programme note:

August 2022,

It has been seven days since the volcanic eruption began in Meradalir. I'm tired after heavy workload the past days. I manage the natural hazard monitoring at the Icelandic Meteorological Office and supervise the monitoring of the ongoing volcanic eruption. My email inbox is full of unread letters. I look at a letter from the composer Veronique Vaka and recall that I had promised her many months ago that I would write a text for her concert program. We don't know each other. We meet on the tenth day of the eruption. I'm on call and can relax a bit. It is refreshing to meet Veronique and I become invigorated when I show her the monitoring room where we are following the eruption. She shines. I sense that she understands as well as I do, that Iceland is no ordinary island. The weather changes quickly. The earth is constantly and often rapidly being sculptured by earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. Landslides and rockfalls, rivers and glaciers shape the land, sometimes in a disastrous way.

The largest and most active volcanoes in the country are covered by glaciers. Grímsvötn is the most remote and active volcano in the country. It is in the middle of Vatnajökull, the largest glacier in Europe and has erupted 60 times since the first settlers came. The glacier is up to a kilometer thick. Like other subglacial volcanoes, it melts part of the glacier, and the meltwater collects inside the glacier ice to form a subglacial lake. When the overlying ice sheet has risen by tens of meters, it reaches the limit of tolerance and the water breaks out in a catastrophic, glacial flood, where the murky glacial water melts its way through the ice and breaks out to inundate the black sands south of Vatnajökull.

It is interesting that we are both working with vibrations, sound waves, but at different frequencies. I tell Veronique about my recent research and that of my colleagues on Grímsvötn. We have found that the ice sheet above the subglacial lake in Grímsvötn vibrates continuously like a membrane. My research group has also discovered a very weak vibration signal that the large outlet glaciers in southern Vatnajökull, Síðujökull and Skeiðarárjökull, cause every year in the fall. We are still investigating the source of these vibrations. A pilot sent me a picture of Síðujökull this summer. He had never seen it like this before. A field of brownish, soft, slush-ice instead of bluish rock-solid glacial ice.

The glaciers are retreating rapidly due to catastrophic warming in recent years. They leave behind unstable slopes which increase the risk of landslides. Furthermore, deep glacial lagoons are left behind that can cause catastrophic floods, not to mention all the volcanoes that are now covered by the glacier. The pressure relief as the glacial load releases will lead to more frequent volcanic eruptions. In other words, the retreat of glaciers will lead to even more frequent natural disasters.

I am glad to have met Veronique and realize that our mission is in a way the same; to interpret glacial processes; me with scientific methods, she with music. The earth does not wait, and I turn my focus back to monitoring the earthquake tremors from the ongoing Meradalir volcanic eruption. - Kristín Jónsdóttir, Seismologist

Neige éternelle, for solo violoncello (2022-23)

Five pieces for solo violoncello

written for Sæunn Þorsteinsdóttir

Neige éternelle: 1. : Premiered on the 30. September 2022, at Norðurljós in Harpa Concert Hall in Reykjavík

Neige éternelle: 2.: Premiered on the 15th of January 2023, in Reykajvík.

Neige éternelle: 3-4-5: Premiered on the 28th January 2024 with Sæunn Þorsteinsdóttir. Cincinnati, USA

Neige éternelle is a series of five pieces for solo cello.

This work emerged after Gemæltan, a cello concerto written for Sæunn Thorsteinsdóttir.

Each piece is an imagined phase in the formation of a glacier.

Erda, double violin concerto (2024)

For two solo violins and small ensemble

Commissioned by Ensemble Storstrøm

World premiere: 28 August 2024, Møn, Denmark, Soundscape by Møn Summerkoncert, 7th Edition. Niklas Walentin, Stéphane Tran Ngoc and the Danish Chamber Players (Ensemble Storstrøm)

Erda is the geologic narrative of the events prior to the 1996 eruption under Vatnajökull and its impact on the glacier. The programme note is written by Stephen Lezak, writer, researcher, and advocate working at the intersection of climate politics and environmental justice.

More so than any other form of existence, glaciers bridge the distance between the turbulent human world and the inscrutable world of the eternal. They achieve this by being simultaneously timeless and ephemeral—inscribing the pre-historic past but threatening to vanish as our planet changes more rapidly with each passing year. And through their double-life, they offer an unparalleled wisdom: the invitation to connect the “deep time” of geology to the diurnal, fleeting time of humanity. - Stephen Lezak, 2024